If a handful of time-travelling activists from our own era were somehow transported into a leftist political meeting in 1970, would they even be able to make themselves understood? They might begin to talk, as present-day activists do, about challenging privilege, the importance of allyship, or the need for intersectional analysis. Or they might insist that the meeting itself should be treated as a safe space. But how would the other people at the meeting react? I’m quite sure that our displaced contemporaries would be met with uncomprehending stares.

It’s not so much that the words they use would be unfamiliar. Certainly ‘privilege’ is not a new word, for instance. But these newcomers to the 1970 Left would have a way of talking about politics and political action that would seem strange and off-kilter to the others at the meeting. If one of the time travellers told others at the meeting to “check their privilege,” it’s not that anyone would disagree, exactly. It’s that they wouldn’t understand what was meant, or why it was supposed to be important or relevant.

We can reverse the scenario, and the picture looks similar. If a group of time-travelling activists from the heyday of the New Left, members perhaps of the Black Panther Party, the Organization for Afro-American Unity, or Students for a Democratic Society, were transported to a political meeting of activists in our own time, they might quickly begin referring to the need to unite “the people” in a common struggle for “liberation,” by constructing “an alliance” based on “solidarity.” In this case, the problem would not be one of understanding, so much as credibility. They would be understood, I imagine, at least in general terms. But would they be taken seriously? The terms in which they express their politics — the people, liberation, alliances — seem like (and indeed, are) a throwback to an earlier era. It seems likely that they would be deemed hopelessly insensitive to the specificity of different struggles against privilege. They would be accused, perhaps, of glossing over key issues of “positionality” and “allyship” by referring not to “folks,” as most contemporary activists would, but to “the people,” as if it were unitary and shared a common set of experiences.

Reflecting on the chasm of mutual incomprehension that divides today’s Left from the Left of the 1960s and 70s, we should resist any rush to judgment. Instinctively, some people — whether out of nostalgia or out of deeply held political convictions or both — will recoil from the vocabulary of today’s activists. There is no shortage of (usually older) critics who complain about the focus on “privilege” and “calling out” in the contemporary activist scene. But we should not be seduced by the broad-brushed dismissal with which these critics, whose political sensibility was shaped (for better and for worse) by the 70s New Left, reject the politics that pervades today’s activist subcultures. We should remain open at least to the possibility that some aspects of the new vocabulary may offer important insights, even if we retain our reluctance to embrace it wholesale.

Conversely, some partisans of the post-New Left will insist that any resistance to the new jargon must be rooted in an attempt to cling to privileges which, allegedly, the new discourse threatens. This, too, reflects a narrow-minded sensibility that renounces the very possibility of learning from engagement with perspectives that contest one’s own basic assumptions. It is this fundamentalist sensibility that has earned “the Twitter Left” and the “social justice blogging community” a sometimes well-deserved bad reputation, but it shouldn’t be allowed to insinuate itself into the real-world activist Left.

In fact, neither of the two political vocabularies considered here should be deemed to be either above reproach or beneath contempt. Both are ways of articulating the politics of people committed to the struggle for social justice, so they deserve, if not necessarily our endorsement, at least our willingness to listen and, where possible, to learn.

Two questions really do have to be addressed, however, in the face of this terminological fork in the road:

- First: why are these vocabularies so different? Does the emergence of the new vocabulary, roughly in the 1990s, reflect a learning process, so that we can think of it as more sophisticated and illuminating than the jargon of the 60s and 70s New Left — the product of a new sensitivity to key issues that were previously overlooked or badly understood? Or does its emergence, with its symptomatic timing in the wake of the Reagan/Thatcher era and the wave of defeats inflicted on the Left in those years, indicate that the new vocabulary is not so much innovation as errancy, straying from radical politics in the direction of a de-fanged adaptation to defeat and political marginality?

- Second: why, if at all, does it matter that they are so different? Are these just competing styles of speech and writing, or do they embed within them contrasting sets of assumptions about the nature of the Left, its main targets or aims, the appropriate way to respond to injustice, and the place of the Left in the wider society?

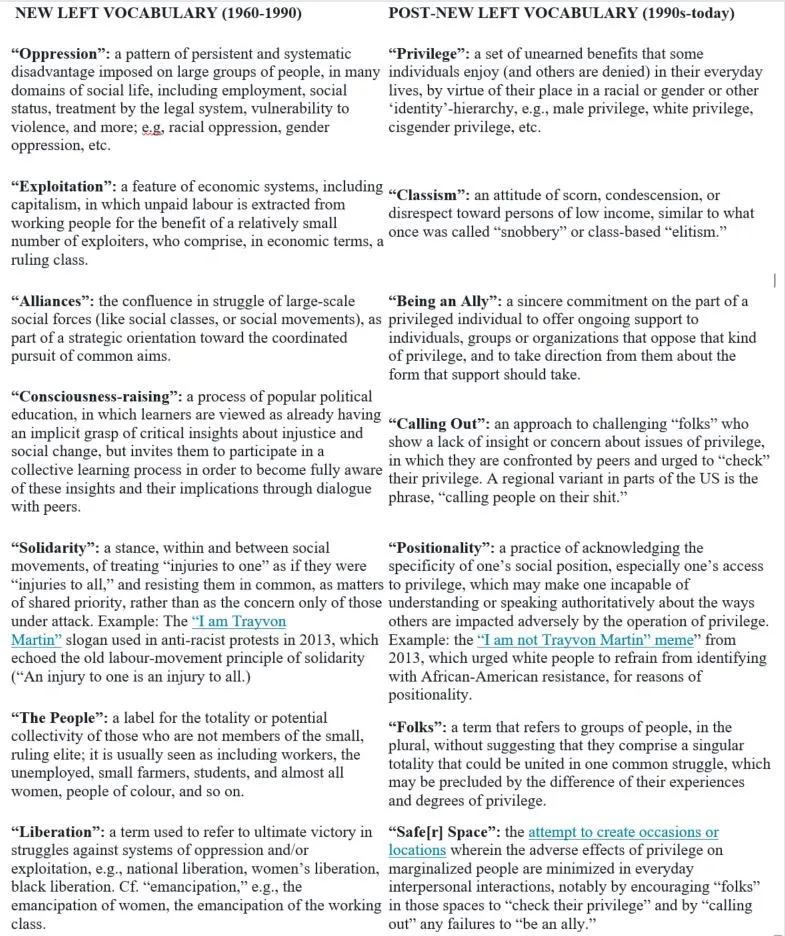

Without claiming to have figured anything out, I touch on both questions below. But before turning to that, we need to get a feel for these two vocabularies, and how they differ. Consider the following table. In the left column, several keywords of the New Left era are listed, along with their definitions. In the right column, each word is paired with a keyword from today’s activist Left, which has largely displaced the older term.

Some immediate caveats and qualifications are necessary, to ward off misunderstanding.

First, the new vocabulary is used almost exclusively by the English-speaking Left in a few countries, especially Canada, the US, and (to a lesser extent) the UK. Elsewhere, such as in Latin America and southern Africa, the Left has its own distinctive vocabularies, which would have to be analyzed separately.

Second, the old vocabulary is still in use today. Indeed, many people use both vocabularies, or at least draw from both, even if they have a primary vocabulary that dominates their speech and writing about activism. But it seems clear that the first vocabulary has faded and continues to fade from use within today’s activist subcultures, as the second one continues to gain ground.

Third, it is possible to use one set of words to express the other set of meanings. That is, one can retain the words, “solidarity,” “oppression,” or “consciousness-raising,” while using them in a way that is shaped by the new vocabulary, so that by “solidarity,” you mean acknowledging positionality; by “oppression,” you mean individual privilege; and by “consciousness-raising,” you mean calling people out. Conversely, one can use the new terms, but give them the old meanings. For this reason, if one hears a contemporary activist use the word, “alliance,” which would be a rare thing, it is worth stopping to ask, Do you mean the confluence in struggle of large social forces like classes or social movements, or do you mean privileged people being committed as individuals to offering support to those adversely impacted by privilege, and taking direction from them? Only in this way can you confirm which vocabulary is being used, strictly speaking.

Fourth, my remarks refer to ‘ideal types,’ not the exact ways that every activist talks. In other words, although my account of the post-1990 activist vocabulary is intended to be recognizable by everyone familiar with contemporary activist subcultures, it is probably a bit more reflective of some ‘scenes’ than others. For example, it will be immediately recognizable, I think, to anyone familiar with the work of Tim Wise, Peggy McIntosh, Melissa Harris-Perry (recently described in The Atlantic as the USA’s foremost public intellectual), or many of today’s ‘social justice blogs.’ but my core contrast (in the two columns) may appear overdrawn and exaggerated to people whose contact with activist subcultures is mainly through grassroots protest organizing. In organizing contexts, most activist speech is infused with a pragmatic focus on getting things done, so some of this jargon recedes into the background. Nevertheless, I would be surprised if anyone (familiar with today’s activist subcultures) claimed not to recognize the terminology that I attribute to today’s activists.

Having said all that, I can now proceed to my two main questions, listed above (why are the vocabularies different, and how much does it matter).

So, why are these vocabularies so different? What accounts for this mutation in the mode of speech typical of Left political activists in recent decades? A close examination of the two systems of terminology reveals some underlying principles that are driving the transformation. In particular, one can discern the operation, just below the surface, of three fundamental shifts.

- A Shift in Priorities from Ultimate Victory to Challenging Everyday Impacts. The older vocabulary looked at capitalism, racism, and sexism (for example) as social systems or institutions that could and probably would be defeated, once and for all, in the foreseeable future. Accordingly, activists of that era defined and described their movements as struggles for “socialism,” “black liberation,” or “women’s liberation.” By contrast, the new vocabulary tends to suspend judgment on (without denying) the prospects for ultimate victory, and to focus its attention on challenging everyday impacts of capitalism, racialization and gender, in the here and now. This prioritization of resistance to everyday impacts infuses, not only the way activists today talk, but also how they choose what to do. For example, what is happening in this meeting, today, is emphasized much more, because it is not seen merely in instrumental terms as a means to destroy systems of domination. The meeting itself is generating impacts that have to be challenged as they arise. Addressing problems of “process,” which once would have been seen as a “distraction” from an urgent liberation struggle, is now seen as part and parcel of what the Left is for.

- A Shift of Focus from Analyzing System Dynamics to Analyzing Interpersonal Dynamics. The old vocabulary assumed that political analysis should study large-scale, often transnational social systems and structures, centuries in the making, e.g., systems of oppression and exploitation. In contrast, the new vocabulary assumes that race and gender and other forms of privilege are enacted in everyday, interpersonal interactions. This is key to the concept of “privilege.” It is likened to “an invisible backpack” of advantages or monopolized benefits that some receive and others are denied. Privileged persons gain these benefits whether or not they even know or acknowledge it. Thus, whereas activists in the late 60s and 70s were keen to use history and political economy to develop a sophisticated analysis of the historical process, centuries-long, that established European colonial domination of much of the world, the new vocabulary both reflects and encourages a change of focus, toward how racism (for example) is enacted or reproduced in the everyday interactions of white people with racialized people, as individuals or in groups. The analysis of the power dynamics of these everyday interpersonal interactions has tended to gain in prominence and sophistication, in parallel to the relative de-emphasis of the importance of political economy and critical sociology within the activist Left.

- A Shift in Emphasis from Commonality (Among Social Groups) to Specificity. The vocabulary of the 60s and 70s grew out of and contributed in turn to the construction of broad-based popular movements, in which hundreds of thousands and sometimes millions of people participated. By contrast, the vocabulary of today’s activists emerged in a completely different, and arguably much less favourable context. One symptom of this is a change in emphasis from the search for commonalities that could be the basis for building alliances and expanding the base of support for militant mass movements, to grappling with the barriers to joint organizing and common struggle. In brief, the old vocabulary emerged in a context where opportunities to encourage solidarity and collaboration were actively sought, whereas the new vocabulary emerged out of the frustration of failed efforts to bridge gaps between people and organizations that reflected real differences. There is a certain optimism in the idea of “consciousness-raising,” or the concept of “the people,” that seems naive and unconvincing to many of today’s activists. The shift from “consciousness-raising” to “calling out,” for instance, reflects (and encourages) a loss of confidence in the capacity of people to learn about, understand and oppose forms of inequality that do not adversely impact them as individuals. These doubts are, in turn, elaborated in terms of positionality and privilege.

Taken together, these three shifts go a long way toward explaining the transformation of the way activists talk, which has been noticeable at least since the 1990s. But is this a turn in the right direction? Or has the activist Left gone badly astray?

As we try to assess both the gains and the losses of this change, it is necessary to acknowledge two fundamental, and incontrovertible facts:

First, it is true that the vocabulary, and the practice, of the Left in the 1960s and 70s had several serious problems. There is no denying the fact that their movements were vastly more potent, and drew in vastly more people from all walks of life, than any political organizing that happens on the Left today, with the possible exception of the Occupy movement during its height. And yet, many people entered and participated in those movements in spite of serious concerns about the persistence, within movement activities, of sexist behaviours and attitudes, forms of machismo that were at once misogynist and homophobic, and ways in which (in some organizations and struggles) college-educated, middle-income white people tended to dominate the proceedings and set the agendas. To the extent that the movement was plagued by problems of this kind, the 60s New Left’s practice belied the radicalism of is official rhetoric, and made its universalistic claims about the “unity” of “the people” ring hollow. It seems clear that the attentiveness in today’s Left activist subcultures to interpersonal dynamics within the movement reflects a genuine learning process. It is a step toward beginning to address problems that were, in effect, glossed over and ignored by phrases like “the people” and a complacent view of the prospects for building genuine “solidarity” and “alliances.”

Second, however, it is also true that the series of shifts from the old vocabulary to the new one has entailed certain losses. In particular, the relative de-emphasizing of system-level causation, in favour of a new emphasis on the importance of individual action or inaction, tends to weaken the integration of everyday Left discourse with the theoretical analysis of systems like capitalism and colonialism. It is true that, in exchange, we have a vocabulary that better enables us to focus on class privilege and settler privilege. But if we are to defeat colonialism and capitalism, we cannot do so one person at a time, or one interaction or relationship at a time. The systems themselves have to be named, understood, attacked and overthrown. This issue is, obviously, closely connected to the loss of a focus on liberation. A liberation focus and a systems focus share a common understanding: that the purpose of the Left is to defeat systems of exploitation and oppression. Challenging immediate impacts is important, but not enough. It is necessary, but by no means sufficient. Moreover, the way we challenge everyday impacts should be informed by our understanding that they are not produced simply by individual actions, but by the operation of large-scale systems. The Left needs a vocabulary, and a self-understanding, that highlights and foregrounds the importance of constructing and expanding anti-systemic movements that aim to defeat systems of oppressive and exploitative power. It is hard not to think that the older vocabulary better expresses this insight, even as it obstructs our access to other critical insights that are also indispensable.

One could certainly say more about the gains and losses associated with adopting either of these two vocabularies. But perhaps it is enough, in the context of a blog post, to have sketched an approach to thinking about the question. Both vocabularies have been formed to address indispensably important concerns, so we should be reluctant to give up on either one. The most important thing, I would suggest, is to refuse to allow either of these two ways speaking, writing and thinking about Left activism to evade the challenge raised by its counterpart. Personally, I would be reluctant to give up an expression like, ‘the people,’ and to take up ‘folks’ in its place. But I hope that the way I talk about the people is disciplined by a certain amount of sensitivity to the motivation that has led some activists to drop it from their vocabulary. On the other hand, I hope that people who have embraced the newer way of articulating Left politics will (begin to, or continue to) see the importance of highlighting issues of system dynamics, large-scale alliance-building, and ultimate liberation, rather than letting these urgently important matters disappear from view entirely.

This is really helpful, thought provoking, serious, I say speaking as an old New Leftie (starting with the Northern Student Movement in 1964) who loves working with twenty-somethings immersed in Collective Liberation. I hope you will post some of your own further thoughts in the comments here.

This does point out the current preoccupation with what are termed “interpersonal” dynamics at the expense of systemic and class based analysis. In the 1970s this was known as identity politics–a politics easily coopted and manipulated by liberals and even the right wing. If system analysis is de-emphasized, I question whether these politics can even be called left.

VERY good point.

I agree with ron j.

Furthermore, from experience in New Zealand, last century “identity politics” often had an effect of would-be activists needing to present a clean-slate of moral/ethical attributes. Even long-gone minor personal infractions and breaches of principle – private included – could be sufficient to needlessly discredit someone. Also, participants in single-issues were often guilt-tripped into levels of “commitment” that were all-too-often based on ad hoc bottom lines decided by liberals with dominant personalities – more than a few of whom have “matured” into conservative and even reactionary bombasts. One effect was political criticism became more frequently directed at individuals rather than as (comradely or antagonistic) polemical left discourse/debate.

Today, “calling out” and various marginal imperatives are too-often directed, ultimately, as focus for attack on a singled-out person – either to discredit one’s “politics” or, worse, to instigate hysterical pack-attack character assassination. In this situation, extreme sub-sets congeal and melt away within which scant selfless solidarity exists = An Injury to One is an Injury to One… This type of practice has to be stopped.

(In my seventieth year), I suggest many contemporary terms/meanings extend what began in the 70s – a descent into post-modernism and individualism which paved the way for neoliberal capitalism. Real tendencies of sectarianism in the left have degraded to the point where “orgs” are often as ephemeral as their rediculous conditional-conformism… Modern terminology, Okay. But one litmus test of a movement is the slogan it displays publicly. I defy any destructive “left” current to march behind a banner e.g. “Check Your Privilege! CIS – No Pasaran!”. Is it necessary to add that much of this is far more important than mere-tedium?

Despite corrosion there are, of course, always those who bravely stand against a hugely powerful enemy. In these uncertain times Unity remains strength. For mine, the principle contradiction remains that between capital and labour. Regardless of how low the ebb, within the broad community of “working people” the working class remains key to counter-attack and revolution. However, isn’t much of what we are experiencing simply regurgitated dynamics of power-seeking groups and ambitious characters – through to agent provocateur mischief?

It’s not over – Workers of the World Unite!

Well said, Ron. The cult of identity politics is one reason why the American left is so marginal. I was in SDS in the 60s and if someone had told me what the “left” in America would look like in 40 years, I would not have believed it.

Kurt Hill

Brooklyn, NY

Thanks for taking a stab at this topic. I think you’ve made some good points. Clearly, as you say towards the end, there is an awful lot more to be unpacked here. I am personally interested in the ways that academic discourse have shaped left discourse. I have suspicions that the current leftist paradigm is strongly, perhaps overwhelmingly influenced by postmodernism and poststructuralism, which arguably became dominant in the 40s with the fade of positivism from Continental European thought. Anyway, I think the ideology associated with mid 20th century Continental Philosophy, which includes things like anti-realism, relativism, subjectivism, and a general skepticism towards science and technology can be more or less directly linked to the trends you’ve discussed in this article.

Although those philosophies also influence the Right too…

This somewhat condescending treatise never once mentions the distributed intelligence of humanity that we have come to understand in the information age. Nor does it deign to consider the Latin American concept of vivir bien, living in balance with Earth, which is now leading social evolution and has no direct connection to the European notion of left. Vivir bien is a way of thinking that still lives even after 500 years of genocidal oppression, purposed to privilege. Vivir Bien is a five hundred year-old language spoken and understood by hundreds of millions, it has regained strength and is shaping those it touches as it evolves to social democracy using modernity and science during an existential crises. Will cosmic powered biology expressed as human prevail ? ¿ Quien sabe ?

Garrett,

I would hold the mirror up to you regarding condescension.

1. The title of the article is “The Rise of the Post-New Left Political Vocabulary”, so I’m not sure what your first point is even about, other than, “This isn’t what I would have written about regarding current political discourse.” Also please speak for yourself regarding what “we” have come to understand about the distributed intelligence of humanity, etc. The two groups imagined in this article might have trouble embracing each other’s language, but you would get blank stares from both of them, not only regarding what you meant, but how it was relevant to their aims. It may or may not be relevant; I can’t judge because I honestly don’t know, and I suspect it would take significantly more unpacking than what the current article achieved for the topic at hand.

2. He explicitly acknowledges that he does not address political language used in Latin America, and implicitly acknowledges it would be worthy of analysis, but again, that’s not what this article is about. Your use of the word “deign” is unwarranted. I am grateful that you have introduced me to the notion of “Vivir Bien”, and I would gladly read more about what you have to say about it. Instead of accusing him of arrogance for not undertaking the analysis he acknowledges is needed, I invite you to graciously provide the analysis yourself as a contribution to the discussion.

You are very articulate and completely correct. Looking in the mirror is a good splash of cold water and in this case was needed even though a year and a half late. Thanks.

Thank you for graciously offering Garrett another path for bringing something new into a conversation. And much gratitude to Garret for teaching us how to receive feedback with equal graciousness. There is nkt enough if this in today’s activist circles.

Reblogged this on All About Work and commented:

This is a fascinating analysis of how language and jargon have evolved across time in activist organizations – and of the influence that language has on organization members attitudes and perceptions (and vice versa).

Personally I find the new language problematically divisive (in the wrong way). Instead of focusing on shared antagonisms the Western Left find themselves separated by a chasm of their own making. One which focuses on difference rather than the shared struggle.

But does this mean that I support a return to the old jargon? No. We need a new way that is able to speak to the great masses of people that are oppressed by our current social order. Until then. Well. I think we will continue to be divided for the benefit of the status quo.

I write more about this modern divide and conquer here: http://alexfelipe.wordpress.com/2013/04/14/divide-conquer-anti-racismsexism-individualism/

Yep. Intentionally so, I figure. #LetsFragmentTheFuckOutOfIt #MaybeItWillGoAway

Thanks for your comment alexfelipe! In meetings sometimes I feel that the attentiveness to group dynamics and privilege tends to make discussion superficial and oriented toward how things are said rather than content. It can be intimidating for someone not familiar with the talk but motivated to make change. My solution is to avoid meetings as much as possible,. talk as little as possible when I have to attend meetings, and reserve my thoughts for a really safe space where I can actually have an exchange. Meetings are only places to plug into tasks that need doing. Any exposure of political thought is unsafe, since mastering the jargon is something that requires several university degrees,or years of practice. If meetings seem like they are not leading to effective action or meaningful tasks, then stepping away in silence is the best strategy. I think that is true of current practices and was true of the old new left. Honchos always run everything, but I prefer to be involved with something effective, and the old new left in retrospective, did extend outward and engage people beyond the political subculture.

Thanks Steve. I find these thoughts depressing though. Meetings should be places where people can speak freely and to learn–but unfortunately here in N. America that is getting to be more and more difficult. I guess that’s why I never became political here… it was experiences in the Philippines that got me plugged in (and even in Toronto I work primarily with Filipino groups–and we’ll make tactical alliances when possible with others). It’s just too ironically hierarchical here (ironic because it’s common to talk about horizontal organization and how no one is a leader–while there clearly being a hierarchy. I prefer things to be explicit.)

Excellent article Alexfilipe. I’ve recently been debating a lot of feminist issues with my sister, and my primary problem with it is exactly that; the divisiveness. I’ve said I have no problem calling myself a person for gender equality, but find even the title “feminist” devisive in a way. Its strange because we agree politically on almost everything but this.

I’ve been told by her friends on occasion to ‘check my privilege’ because im white, male and straight; friends who I’m sure I’d agree with on every other political issue entirely, but MY privelege is what should be ‘checked’ or focused on?? I mean, forget the fact that I grew up in a trailor park in a single parent household, I better recognize that some people have it worse than me, and focus on this difference if anything is to change??

You’re absolutely right, the loss of solidarity is a sad thing. The power elites have gone to great lengths to atomize, and its working.

Anyway, I’ll stop before I start rambling.. Anyway.. Great article. Thanks.

I used to feel this way (similar background). Until someone said this to me: “Yes, you have suffered prejudice or discrimination AND you are white, male and straight. However, you are likely to have never suffered prejudice and systemic discrimination BECAUSE you are white, male or straight.”

Yeah I agree with you, it’s a very good article!

I appreciated the use of language as a vehicle for this discussion. For the author, and those who are interested in and critical of the new wave anti-oppression activism, I highly recommend this: http://libcom.org/library/who-oakland-anti-oppression-activism-politics-safety-state-co-optation

I owe much to identity politics as a lesbian but the elephant in the room is the decline of labor and now the disappearance of the middle class. solidarity vanished and identity politics prevailed. Now the struggle against poverty is a personal one. Bummer!

‘disappearance of the middle class’? Don’t you mean working class?

What the author of this article is really saying is that they don’t actually want a better world. They don’t want to stop the ecological destruction that is endangering the planet’s ability to support life, they don’t want to remove the banksters from power, they want the corporations to continue on their expanding project to control and commodify every single aspect of our lives. But they want to pretend that they’re opposed to these things, but that we can’t oppose those things and actually remove the wealthy elite from power until we waste lots of time niggling around making statements about stuff that none of us are actually in a position to do anything about until we unite in common cause and remove the wealthy elite from power.

But that’s the point. That’s the reason university indoctrinated paid professional activists push microscopic differences into the forefront and demand that everybody change everything about our interpersonal relationships before we’re ‘good enough’ to remove the elite from power, because the wealthy elite own and control our universities, and the purpose of this divisive rhetoric is to buy the elite time to give themselves more control and prevent themselves from being removed from power.

My only question is, does the author know they’re sabotaging humanity’s hope, or are they so brainwashed into these racist religious doctrines that they really aren’t capable of unity?

Tides and Ruckus are funded by major corporations… to overthrow corporate rule?

Did you read the same article I did? WTF are you talking about?

The author is pretty clear that the post-new left is having that problem, and that he believes the (old) new left’s concepts had a stronger element of big progress and attacking of structures. You’re way off-base. Even when it comes to the post-new left, you’re way off-base. It’s not at all that we’re “not good enough” to remove the elite. It’d be more accurate to say the post-new left is fracturing itself by defining so many types of oppression and perpetrators of that oppression. I think that’s an accurate statement, but it’s not like those people don’t deserve dignity and justice simply because if they shut up and cooperated, we might have a bigger, more solvent mass.

I think telling someone what they are “really saying” shows why this switch in language was and is so necessary. The revolution didn’t happen in the 70s and by abandoning the hard won lessons and returning to class reductionism I’m not that sure it’ll happen today. We haven’t figured out a way to call people out and keep everyone in the room and that looks a lot like earning street cred rather than politics. But false consciousness isn’t the answer.

Daniel Johnson has a pretty good take on this. It seems to me, though, that the author left out one important term from the earlier period, “guilt-tripping”. That is, making accusations against individuals based not on their work but on inherited characteristics like class at birth, education, gender, and race. I know of one case in the 70’s when a would-be party engaged in a continuous orgy of this until it completely disintegrated leaving behind nothing but broken individuals. If you were an infiltrator and you wanted to incapacitate an organization, wouldn’t this be a dandy way to do it?

You hit the nail on the head, Jerry. Distributed intelligence speaks many languages and experiences. A new and modern democracy is needed to focus human intellect at a time of existential specie crises. Democracy is an organic tool of cosmic powered biology.

Yesterday Pete Seeger died, he was 94.

Listen to his music and everything falls in place.

You, the young generation of today is, and was not the only one with those concerns.

Go from the early times through the French revolution to Rudi Duschke in the sixties, Bob Dylan and all the folk singers from the sixties and seventies you will find that your generation has a lot in common with previous ones, like the one who stopped the Vietnam War.

I would like someone who advocates this post-new left thinking apply their approach to the departed white man, Pete Seeger and after that to the black man, Martin Luther King.

“The analysis of the power dynamics of these everyday interpersonal interactions has tended to gain in prominence and sophistication, in parallel to the relative de-emphasis of the importance of political economy and critical sociology within the activist Left.”

Not much to disagree with there, but I think don’t think that privilege *has* to be individualized. At its best, it can be an expansion of the concept of oppression by making the invisible aspects more visible. For example, within a framework of oppression, it’s easier for me as a white dude person to say “well *I’m* not oppressing you,” whereas the term privilege makes my complicity visible. Where things fall apart a bit is in the analysis of how to respond to that. Feel guilty all the time? Use the privilege for good? Become totally demobilized and step aside to make space for others? Some of the above, at the appropriate moments? My sense is there’s no widespread, common, easily-understood version of what to do with privilege, other than to continually fess up that one has it.

Andrea Smith’s recent intervention goes some of the way to addressing these issues (http://andrea366.wordpress.com/2013/08/14/the-problem-with-privilege-by-andrea-smith/) but it’s not easy to package. I think that’s largely because we’re struggling with vocabularies and concepts that have been shaped by a combination of manichean categories of good and evil, and the logic of consumption and individualism. That, I think, is at least part of the reason why going outside of those categories feels so mind-bendingly painful, and why we revert to individual versions.

Reblogged this on The Red Plebeian and commented:

I think this is a very interesting take on the issues related to the current post-modernist infused discourse in left-wing radical circles. That though there are certainly issues with the New Left movements of the 1960s-70s that the post-modernist Left in the 1990s attempted to address, there is a problem that in the antithesis process the final goal of actually doing away with the status quo was lost. There needs to be a synthesis

Have to say it sounds like the language of defeat to me. The goal is still to leave capitalism behind. If that is not our goal, aren’t we collaborating?

Appreciating this piece so much! Let’s get wise to privilege, specificity, and interpersonal impacts so that we can get the proletarian socialist revolution on and poppin! 🙂

deep bows.

The vocabulary is changing because the Left is losing the intellectual argument. There is no oppression; only privilege. There is no exploitation; only classism. There are no alliances; only allies. There is no ‘consciousness-raising;’ only ‘calling-out’. etc.

The Left is losing, and its time is almost up.

Well said, Snowdog. This stuff is profoundly reactionary and really not some kind of academic accident.

I think the focus placed today on interpersonal relations is important, but it can also be overdone. Sometimes, this concentration on challenging systems of domination on an interpersonal level can lead to an overemphasis on process, and the proliferation of ‘group-think.’ I still think it is productive if done correctly, though. This is my experience and I’m interested to hear if others share these sentiments, or completely disagree.

I’d hazard the opinion that the central problem here is that a real commitment to systemic or structural critique is at loggerheads with, and perhaps ultimately opposed to, an ideology centered on liberation. Indeed this is the deep problem of the left that Foucault sees in the work of his biggest influence, Althusser. Foucault wrestles with it honestly and heroically but is finally unable to resolve it.

I’m glad to find this (via Facebook, where else.)

I’ve been paying more attention to the newer language lately. However I grew up with both—reading zinn and Chomsky, Michael albert, and hanging with lots of activisty types in high school and college.

I’ll give credit to a couple old heads of the new left for helping me form my position on this—staughton lynd and Michael albert: I think these vocabulary differences trace back to the history, as you suggest. The climax of the new left was a massive raising in the consciousness of the people followed sharply by their massive outpouring of rage.

For the last forty odd years, many smaller groups of folks have retreated into their comfort zones, highly attuned to checking the privilege of any who enter.

My personal soft spot for the old heads must be pretty obvious. But the truth is that I really think the last forty years *have* been a step forward.

As I see it, and as you allude to at times, the emotions and singular, laser-focused purpose (end the war, end jim crow) meant that people put their conflicts and reservations, even common sense and dignity/integrity to the side for the revolution. Admirable perhaps, foolish probably, and doomed to fail without doubt. Since then, we’ve been trying to figure out how to put the pieces back together. And I think comfort and safety are pretty important for clear thought, building close bonds, and longevity of commitment.

So yeah. History doesn’t really repeat itself, and that’s a good thing. I’d be damn disappointed if it wasn’t any better than TV.

I’m glad to find this (via Facebook, where else?)

I’ve been paying more attention to the newer language lately. However I grew up with both—reading zinn and Chomsky, Michael albert, and hanging with lots of activisty types in high school and college.

I’ll give credit to a couple old heads of the new left for helping me form my position on this—staughton lynd and Michael albert: I think these vocabulary differences trace back to the history, as you suggest. The climax of the new left was a massive raising in the consciousness of the people followed sharply by their massive outpouring of rage.

For the last forty odd years, many smaller groups of folks have retreated into their comfort zones, highly attuned to checking the privilege of any who enter.

My personal soft spot for the old heads must be pretty obvious. But the truth is that I really think the last forty years *have* been a step forward.

As I see it, and as you allude to at times, the emotions and singular, laser-focused purpose (end the war, end jim crow) meant that people put their conflicts and reservations, even common sense and dignity/integrity to the side for the revolution. Admirable perhaps, foolish probably, and doomed to fail without doubt. Since then, we’ve been trying to figure out how to put the pieces back together. And I think comfort and safety are pretty important for clear thought, building close bonds, and longevity of commitment.

So yeah. History doesn’t really repeat itself, and that’s a good thing. I’d be damn disappointed if it wasn’t any better than TV.

Really thoughtful post, thank you. In his most recent book, The Language of Contention, Sidney Tarrow theorizes about “repertoires of contentious language” in a more general way that you might find interesting. He focuses on the “symbolic resonance” and “strategic modularity” of particular words and phrases as parts of the story of their adoption and diffusion, and he talks about how those vocabularies co-evolve with organizational forms and modes of interaction with government authorities in which those vocabularies become embedded, sometimes productively and sometimes not. Anyway, I think your ideas implicitly or explicitly incorporate much of what Tarrow discusses in that book, but you might enjoy reading it anyway.

Reblogged this on Ken Nero's Blog and commented:

Very good discussion pertaining to the language of leftists today and of yesteryear.

Sometime in the 1960s Stokely Carmichael, leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, said “The position of women in the SNCC is prone.” One great left-wing folk singer of the time ranted about how women’s liberation was a CIA conspiracy to divide the movement. Sexism in the “new left” of the 1960s was certainly a very serious and vile problem.

But how do you deal with sexism, racism, homophobia and transphobia in the workers’ movement? This new vocabulary which the author so clearly lays out in the light of day carries some insights but in the main is useless.

But I’ll tell you what this vocabulary is very good for: to serve as a smokescreen under which burnt-out lefts can retreat to liberalism. I know a chap who for some reason still calls himself an anarchist, even though he hasn’t said anything about class, austerity or the workers’ movement in about three years. His politics amount to an extremely pedantic version of liberalism, complete with a relentless mocking of anyone with a revolutionary bone in their body.

I think we all know a few people like this – trying to catch the fast track to academia, no notion of advancing the class struggle or building a revolutionary organisation. Read more books by bourdieus and baudrillards than they’ve had conversations with working-class people.

The key insight in any left-winger’s political development is that the most serious problems facing our species are systemic, not personal. The new vocabulary is, in the main, a retreat to the personal. Thank you for helping me see that more clearly 🙂

Totally agree: nomenclature for middle class narcissists influenced by “one little candle” political ideas learned in Sunday school and bolstered by the New age.

“Positionality”, really? This sounds like something an insecure person would come up with to sound smart. One doesn’t change the world by arguing semantics. Why not just use straightforward language? Listen to the words of Bob Marley, Pete Seeger, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. A simple message of justice and equality is enough for most people.

Thank you for a good article. Language is so important in so many ways. What I take away from it is that the post-Left of the right column reflects defeat, a retreat, avoidance of confrontation and a reluctance to clearly speak. The search for new language is not just because the existing is not working anymore. There is the issue that the democratic party, the republican party and the U.S. government are in constant search of new language, much of which they steal from the commons and put new meaning to, The new meaning is always to shape people to their particular self-interested goals to maintain or gain power. The republican party spends billions to do this, and the democratic party is not that far behind, increasing over the last few years. Obama stole the word hope and eventually changed its meaning to, false promises. A betrayal to humanity. Many levels of the republican party stole the word, grassroots, well, from the grassroots, and then proceeded to exploit it to shape people in numerous campaigns that attacked the grassroots. Grassroots is another word that could go in the right column for the modern equivalent of the word, people.

I’ve noticed that after a strong generation there are one or more weak ones that focus on the issues in other less apparent ways. It’s not something for which to blame the weak ones. It is just a natural rhythm of life. There’s push and retreat, push and retreat repeated forever. I think the next generation, maybe the Millennials, will kick ass. I think some really huge advances will be made, starting in about eight years and last for about 20 to 30 years. It will undo some of the more oppressive, authoritarian dynamics and laws of these times.

I would say, to rejuvenate the Left,, but that’s not going to happen. There has been a huge impact to the political spectrum that is rarely addressed, yet constantly happening and growing, to which the Left is blind to. The Left can’t go back, and it will not be able to go forward. I’ll save that for another post.

in other words, the rise of the “post-new left” (eeeeckkk) is a shift from collectivism to narcissism.

sorry that was vague. i agree with the many of the other comments. this new vocabulary does indeed carry the influence of postmodern philosophy, which i think to be an unintentional consequence of the great postmodern thinkers. it is nonetheless a pessimistic language of defeat and fatalism. it seems to have more to do with finding personal comfort (hence narcissism) in the present political climate than it does to do with implementing actual political change. i.e. there’s hardly anything political about it at all. i think the majority of actual political organizations and non-profits (from radical groups like the ISO to more mainstream ones like Free Press Action, to name just a random two) reject this sort of terminology.

Here in San Francisco, I find that this language is prevalent within the nonprofit social service provider and affordable housing developer community and absent outside of it. The focus of “the left” has switched from contesting the dominance of capital in public policy to accommodating capital on its terms and merely mitigating some of its worst excesses for some people. Poverty mitigation in lieu of even liberal equity in public entitlements.

Given that the nonprofits are dependent upon grand and public sector funding, they serve those two masters first. When their funding chain is yanked, the nonprofits will sabotage any popular demands by creating the illusion that “the people” whom these entities claim to speak for oppose anything too “radical” such as parity between give aways to capital and take backs to the public sector. Parity, as in liberal equity, is now deemed too radical a position to consider under neoliberalism.

This arrangement has been in place for three decades now and has proven itself as a structural means of cooptation of popular resistance to capital’s rampage. One tool that is deployed is the language segregator that ensures that only those who speak the proper language, arbitrarily and capriciously defined, are allowed to play. In a racist, sexist and homophobic society, we’re going to have to learn to organize with racists, sexists and homophobes without losing our shit. This was glaringly apparent in the “anti-oppression” working group at Occupy SF.

Lesbians and gays did not achieve overwhelming public support by yelling at people for not liking us. Over a period of decades, we came out in increasing numbers, to our families, friends and coworkers, leading by example. This was a completely anarchistic, uncoordinated, spontaneous emergence of an empowered community from an oppressed community. That is the model of emancipation that has worked in our lifetime once the system adapted an immune response to traditional direct action and top-down authoritarian political organizing.

That said, does anyone really care what a Cult in service of a newspaper and politburo like the ISO thinks?

Yes!

There’s another relevant angle: The population since the Left of the 60’s in the U.S. has doubled. The world population has more than doubled and will soon be more than tripled. From then till now the number of non-profits and their employees and volunteers have sky-rocketed. In 1960 they comprised about 3 percent. Today it’s about ten percent. The seriousness and awareness of issues has increased. Communication about it has increased. Despite that, there has not been much success. Instead of completing an issue and removing it from the stack, it stays in the stack with many more being always added to the stack. It is overwhelming. The new lexicon of the right column without addressing these root causes instead seems to be grounded in a protective coping mode. The Left and activists of today will not raise the possibility that it may be hopeless. Such realistic opinions are not popular in the forced optimism of these times.

The non-profits are a tactic of power designed to insulate itself from demands from below by creating a dependent class of coopted “activists” which it can control. We will not be able to get a (nonviolent) clear shot at power without shooting (nonviolently) through our putative allies who claim to speak for “the people” yet who hold the majority of “the people” in contempt for not meeting one of the spectrum of politically correct privilege or language tests. Not contested, of course, are the actual real consequential actions against working people that this insulation allows to roll forward mercilessly.

There is little leftist going on here, unless a complete redefinition of class from labor/capital to people like me/anyone who doesn’t “like” people like me qualifies as leftist class analysis these days. I have always wanted to use the phrase “solipsistic narcissism politicized” in a sentence, thanks for the opportunity.

Cumbersome language is not unique to the “post new left” (see?)

Pretty much any inbred socialist clique, I mean political party, suffers from this problem. Really it’s common in exclusionary groups of all kinds.

This stuff isn’t necessarily apolitical, unless you want to throw the beloved civil rights movement under the bus. Which you probably could, those commie pacifists would let you. God bless them.

Look– how we behave as individuals is–hmm, how do I stress this enough… *really important* . Chomsky or Zinn, hell Marx will tell you that.

Like, insulting one’s political allies in a noticeably cruel and vicious manner: probably not a good way to build a movement of the people.

As a queer, I see a significant dissonance between the identitarian language of the advocates, activists and academics (AAA) on how queers should see ourselves on one hand, and how queers outside of the activist milieu actually see ourselves on the other. I observe the same dissonance between the AAA of color and women and non-AAA women and people of color I mix with in my own life.

The drive for most folks is taking pride in their perseverance over adversity rather than wallowing in their victimhood. Given the risks that those who came before us took to achieve for us the freedoms we now enjoy to have these conversations, Stonewall, Compton’s and the civil disobedience of the civil rights and women’s suffrage movements, today’s AAA are unworthy heirs to the sacrifice of previous generations.

It is not like these issues were not discussed three decades ago. But it became clear that that language did not resonate so most of moved on. The last thing I need to hear from some wet behind the ears AAA is how I “don’t get it” on my “privilege.” Yes, I “get it,” i simply disagree with being forced down a dead end alley that we know is a dead end. Identitarianism is a dead end.

To my mind, this is a product of the self esteem and play date culture in which the millenials were raised. During Occupy SF, they created an “anti-oppression” caucus for queers, women and POC. Only 10% max of queers, women and POC participated, most of us were comfortable working in mixed groups. If you can’t work in a mixed group in the Bay Area in 2011, then the problem is with you, not the greater culture and you should probably seek counseling to get over your issues.

Well I’ve really been spoiling for a fight on this topic (or at least a conversation ;-), but no one’s bitten on my general posts. So I guess I’ll get in your face, you seem like you want to talk about it too…

Pretty much agree with you about nonprofits as a coopted force. Ditto for Cult of ISO.

But I do find your language insulting. I don’t think telling someone to get counseling for their issues is particularly effective at building alliances with them. Yet you insist we need to be building alliances with even racists, sexists and homophobes, presumably people who are even more of a pain in the ass than these coopted liberals.

As an aside– did I read your article in this little local publication I found in the anarchist bookstore on my recent visit to SF? It was talking about the anti-oppression caucus at Occupy SF and describing their obnoxious shenanigans. I liked it.

Glad I found your blog. I appreciate the depth and detail that philosophers bring to socio-political issues 🙂

For years I have found that nearly every ‘alternative’ meeting I’ve attended has given priority to people who insist on educating everyone else about the language that they use, or even the body language they are allowed to use. The result has been a profusion of jargon that has put working-class people off attending, and has made many of them more comfortable with the politics of the Right – which is happy to use far more straightforward language in order to get people involved. By your fascination with language, rather than events, you may be falling into the same trap.

Reblogged this on Edicio dela Torre and commented:

Fascinating and thought-provoking. But as Stephen says, the post-New Left political vocabulary he cites is more present in North America and the UK. It would be interesting to explore the equivalents in the 1970s Pilipino vocabulary of activists, and in post 2000 Pilipino activist vocabulary.

I’ve been involved in a lot of discussion in the modern left and I think that the article elides a lot of actual facts about the left and discourse among leftists to create an illusion of a homogenous undifferentiated group of people who all focus on the same things in the same way. This makes the critique somewhat questionable as it does not seem remotely relevant to the discussions I am a part of. Yes, there are people who focus on interpersonal dynamics and relationships as the locus of oppression, but these are by far not the only people. Many of us have a systemic approach and understanding that is entirely ignored here.

I have been thinking about this issue a lot and following some of the young ones on Twitter. I do think academia shaped alot of this discourse focused on individuals. The thing is that the issues that divide us- racisim, privilege, homophobia, sexism, classism, – MUST be worked out together in Struggle together. As a former union organizer in the South, I saw workers unite together against capital, and yes we had hard moments and workers who distrusted each other because of years of racism, etc, but we all wanted to win a collective voice and this helped us unite. The problem now is that sometimes these Twitter fights and calling each other out business happens without struggling together towards our common liberation(some vintage language).

I saw this kind of insistence on perfection of vocabulary destroy the most radical segments of Seventies and Eighties Feminism. I just watched a strong local group destroy itself with the same process. I suggest that any of you working in groups in which political correctness is beginning to take up most of your communication, identify who of your members is most consistently calling-out others on their privilege AND consider whether that calling-out is strengthening or weakening your group. While we are insisting on getting it perfect with each other, the Enemy is steam-rolling merrily along – over us, the earth, water, creatures and the rest of our species.

Reblogged this on Radically Mad.

Fantastic site. A lot of useful info here. I’m sending

it to several buddies ans additionally sharing in delicious.

And of course, thanks in your effort!

Fascinating to see the differences yet despite all this we have to continue teh struggle for total human liberation

Reblogged this on Black Hypatia and commented:

Excellent analysis of the differences between the language used by the New Left and the post-New Left.

Read- Galileos Middle Finger by Alice Dreger.- It’s a terrific book about how identity politics is having a poisonous effect on science and the media. Shes a lefty but I think people of all types would love this book. Telling someone to ‘check their priviledge’ is a great way to lose an ally. You coax allies, you show allies, you don’t alienate allies. Im finding the kids (like all kids their age) seem to think they are inventing the wheel. Both in experiences, and words/concepts. I agree that it’s time groups find ways to work across ideologies on things they agree on.

Mary Sorjourner – You are so so right.

Oh, blah, blah, blah. Had too much of this in the 70s. Actions unite. Words divide.

Reblogged this on Workers BushTelegraph and commented:

Not sure this applies to the Australian context, the language that is. Also I doubt the problems of the Left are down to language and generational differences. A good article worth reading, nonetheless.

Class (and class struggle) doesn’t really get a look in (in either column) does it?

Re: the comment that “Class (and class struggle) doesn’t really get a look in (in either column) does it?”

I don’t know why you would read the text in this way. It seems like a strange reading, a misreading if I may say so. Certainly, the word “class” is used four times in the two columns, not counting related words like “classism” and (more importantly) terms like “workers” and “working people,” which also appear in the columns. But let’s remind ourselves of how class figures explicitly in the two columns, not just in being mentioned, but being addressed in certain clear and explicit ways (which doesn’t mean it is addressed in ways that are problem-free, etc., but that’s another issue).

First, “exploitation” (left side) is defined as “a feature of economic systems, including capitalism, in which unpaid labour is extracted from working people for the benefit of a relatively small number of exploiters, who comprise, in economic terms, a ruling class.” That’s a pretty straightforward reference to class, obviously. On the right side, it is contrasted with “classism,” meaning “class-based elitism.”

Second, “oppression” (left side) is defined as “systematic disadvantage imposed on large groups of people, in many domains of social life, including employment, social status, treatment by the legal system, vulnerability to violence, and more.” Speaking personally, I regard the working class as an “oppressed class,” in this sense, a point that I have elaborated in another blog post, so I regard this as covering class oppression. On the right side, it contrasts with “privilege,” and those using this vocabulary routinely talk about “class privilege,” which they usually use to mean advantages (especially with respect to how one is treated or represented) that derive from one’s relatively high income, or at least one’s not being poor. (As always, in this context, the question of whether class is addressed — which you comment raises — has to be treated separately from the question of whether it is addressed in the best way).

Third, “alliances” (left side) are defined as “the confluence in struggle of large-scale social forces (like social classes, or social movements), as part of a strategic orientation toward the coordinated pursuit of common aims.” Obviously, “the confluence in struggle of social classes” is an aspect of class struggle, so the point makes itself.

Fourth, “the people” (left side) is defined as the “potential collectivity of those who are not members of the small, ruling elite; it is usually seen as including workers, the unemployed, small farmers, students, and almost all women, people of colour, and so on.” This, in my view, is a political (not narrowly economic) class concept, derived (I would argue) from Marx’s concept, in Capital, volume 1, of the “Volksmasse” [mass of the people], which he says has its labour and agency “expropriated by a few usurpers” under capitalism.

Fifth, “liberation” (left side) is defined as “ultimate victory in struggles against systems of oppression and/or exploitation…. Cf. ’emancipation,’ e.g., the emancipation of women, the emancipation of the working class.” Obviously, the notion of the self-emancipation of the working class addresses class.

Finally, sixth, the concept of “solidarity” (left side) is defined as treating injuries to some as if they were injuries to all, and struggling in common against them on that basis. Clearly, this is in part a reference to class solidarity (although not exclusively to class solidarity).

So, perhaps you skimmed the post rather than reading it, but I would think a more careful reading would put your concerns to rest.

Yeah very good review of an important topic.

I think you identify well a real split. On the one hand are people who tend to focus on immediate problems, highlight differences between groups and how different groups face different forms of oppression, and emphasize individual responsibility for addressing social injustice. This group tends to be younger and adopt the newer vocabulary. On the other hand are the people who tend to be older and adopt language from the earlier “new left” era of activism. These people tend to focus on the systems that oppress all of us, highlight how the systems create common class interests among the oppressed, emphasize building unity and acting with solidarity for others who experience oppression.

OK, I think you are right that both perspectives/approaches have something to offer as well as weak spots or drawbacks. Yet I also think you are missing how much agreement already exists. Take the issue of police brutality for example. I think there is broad agreement on the left at this point that police brutality is a problem. Solutions that tend to be popular among many different people: civilian oversight of police, more community engagement, legalizing drugs, clearer guidelines for police conduct, better prosecution of police and harsher punishments when they commit violent crimes.

The problem comes in actually figuring out how to achieve these demands. Some think we need to march and protest, others say we need to vote, others think civil disobedience. Then you have all sorts of infighting in meetings and disagreements about minutia like the language of the list of demands that will go on the website.

I live in Seattle. I’ve been to a few meetings and a workshop put on by the local restorative justice group. A lot of people in it are involved in local activism regarding police and prisons. One of them, a lawyer, told me she has actually talked to people in the city or county who expressed a willingness to do a pilot where they would try restorative justice practices instead of the normal trial and prison approach. So this would involve face to face meetings between the victim and perpetrator to sort out how to make amends for the wrong done.

I offered to help with making this a reality and I’ve never heard back. And remember, this is an offer from the people they are fighting to actually meet one of their central demands. This is an opportunity to do the work that they say is the purpose of their organization.

I can tell you a lot of other stories from my involvement with various activist groups. In my experience people have really very little idea about how to effectively accomplish political change, and this is not the exception, it is the rule.

The ‘language of the new left’ is the language of university educated middle class power-players for whom political action ‘resisting’ the system is just part of their training for a place of authority within the system. The middle class ‘radicals’ have used identity politics to derail efforts to unify poor and working class people on common ground, driving low income white people to the right wing because they are blatantly disrespected almost constantly by privileged middle class pseudo-radical elitists who use the various ‘privilege’ narratives as a tool to protect their own middle class economic caste privilege.

I know no one is reading this thread anymore but I only just now discovered this article. It’s a very good attempt at evenhandedness examinig two different sets of left jargon. I can only speak as a biased 56 yr old – female, feminist, working class, socialist/anarchist. Yes, and white. While I’m well aware of the limitations and hypocrisies of the language & vision of the old New Left, the language of today’s identity-obsessed so-called “left” fixates only on separation to the exclusion of all else. All I see is a language and analysis of competition between who endures more oppression, who has used the wrong language, who has been abused & harassed on social media, which celebrity is “empowering” or whatever. It is a sensibility that is totally immersed in and cooperative with establishment capitalist culture and politics. It offers no challenge to or critique of powerful political and economic institutions.

While the old language did not adequately address gender & race distinctions, at least its ultimate aim was human solidarity, *bringing people together* who endure oppression. It was a sensibility that was highly skeptical of or outright rejected powerful institutions like the military, both political parties, corporate America, etc.

I find words like “allyship” so utterly absurd and pathetic, by the way. Weak sauce, lame, no heft or weight at all, no substance. A pathetic replacement for “solidarity.” Today’s identity-ONLY politics has no vision of confronting institutions and systems–its only vision is to tell people to “check your privilege” and elect Democrats who are not white and male and straight. That’s it–scolding, lecturing, being snide & snarky on social media. There is total indifference to economic issues that destroy people’s lives, and absolutely no interest in militarism and imperialism. To the contrary, any concern for such politics is labeled as “white privilege” issues. There is no sense of human solidarity across borders whatsoever, no universalism, no internationalism. And there is only hatred of the white working class. Stories of poor white people committing suicide only generate ridicule and celebration.

The result is an objective support of a corporate-owned Democratic party, support for destructive environmental policies, support for war war war etc. There is plenty to criticize the old New Left with – but I much prefer its international anti-militarist anti-capitalist vision than a myopic insular “left” that has nothing to say about war, imperialism, militarism and corporate oligarchy. And that actually identifies Hillary Clinton as some kind of hero for anti-racism pro-woman policies.

I do not, btw, include a movement like Black Lives Matter in this. That is a genuine movement of substance responding to savage daily racist brutality by law enforcement. I have only admiration for the young people on the streets in that movement confronting a police force that looks like a frightening vicious occupying army.

I’m still reading it. And I agree entirely. Those attempting to oust Corbyn from the Labour leadership in Britain have been obsessing over identity issues – and in some instances have conveniently invented episodes of bullying linked to their membership of a group with a particular identity. Connected with this is a concerted attempt to portray the working-class, and particularly the working-class left, as ignorant, prejudiced and misogynistic.

Very well said!

THE ORIGINAL POST: The vocabularies used by both the new left and the post-new left both reflect worldviews that have valuable things to offer, while at the same time each has limitations and disadvantages.

90% OF THE COMMENTS: I agree, left kids today (if we can even call them “left”) are complete garbage.