In the marxist tradition, fascism has typically been understood in terms of a vulnerable ruling class seeking recourse to a populist ‘strong man’ in the face of the threat posed by the organizational power and grassroots militancy of the working class. In the context of a weak and unstable liberal democratic constitutional regime, which limits its capacity to crack down on dissent, capital resorts to an emergency terror, carried out by a demagogic proxy regime, in order to break the resistance of working-class movements (labour and socialist parties, trade unions, workers’ councils, feminist, anti-racist, and national liberation movements, and so on). The aim is to restore capitalist hegemony on the back of a superficially ‘anti-establishment’ but de facto pro-capitalist reign of terror. This approach to understanding fascism, which obviously takes the “völkisch” fascism of Weimar Germany that culminated in the Third Reich as its paradigm or prototype, is rooted in the analysis of right-wing populist ‘strongman’ crackdowns developed by Marx in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. The understanding of fascism that emerges from this line of thought is typified by that of Trotsky, who said that “the historic function of fascism is to smash the working class, destroy its organizations, and stifle political liberties when the capitalists find themselves unable to govern and dominate with the help of democratic machinery.”

Asymmetric Polarization

As of right now, at the end of October 2018, Trump’s favorability rating is more than 5 percentage points higher than it was when he was elected. His victory was no fluke or freak accident. Nor can Trump’s rise be explained in terms of US politics alone. Rather, it typifies a global trend toward far-right, nationalist, racist, anti-worker forms of authoritarian populism, from Erdogan to Bolsonaro, and from the DFLA to the Proud Boys. It is urgent that we understand the dynamics of this dangerous development. Unfortunately, the ‘classical’ marxist analysis of fascism sketched above may not suffice for this purpose, in this new and different context. For one thing, in our time the rise of far-right authoritarian populisms is in most places not taking place against the backdrop of powerful, insurgent workers’ movements. On the contrary, unions and labour parties, and left social movements generally, are weaker than they have been for many generations, and they pose a very limited threat (in the short to medium term) to capital. Further, it is apparent that today’s far right has a distinctly non-classical aspect insofar as — notwithstanding the unconvincing and half-hearted anti-’free trade’ rhetoric of Trump and others — the new far-right authoritarian populisms are fully committed to an intensification of neoliberalism. The flirtation of early fascism with anti-socialist forms of ‘corporatism’ and authoritarian state planning, familiar from the 1920s and 1930s, is nowhere to be found even in the rhetoric, much less in the practice, of the regimes and movements of the contemporary far right. Today’s rightist, racist authoritarianism is clearly as supportive of the neoliberal policy agenda as it is of capitalism as such.

It should be said that, even if the far right’s recent rise is evidently not a response to working-class insurgency, the political context today is not simply that of an unchallenged right wing resurgence. Rather, the situation is one of asymmetric polarization: both the anti-neoliberal left and the white-nationalist right are growing, at the expense of discredited centrist political parties and currents, but only the growth of the far right has been reflected in widespread electoral successes, and this fact seems to register a comparatively stronger upsurge on the far right and certainly puts greater momentum and resources at its disposal. Even so, the growth of the anti-neoliberal left is indeed a mass phenomenon (in some places), typified in the US by the remarkable increase in membership of the Democratic Socialists of America, and in Britain in the shockingly unexpected sharp left turn of the Labour Party (!) under Corbyn. In a 2018 Gallup poll, Americans expressed a more favourable view of socialism than capitalism. According to Gallup, “Americans aged 18 to 29 are [more] positive about socialism (51%) [than] they are about capitalism (45%). This represents a 12-point decline in young adults’ positive views of capitalism in just the past two years and a marked shift since 2010, when 68% viewed it positively.” These numbers are obviously limited in their significance, because they leave terms like socialism and capitalism undefined. If ‘capitalism’ is replaced with ‘free enterprise,’ it instantly becomes much more popular in opinion polls. But they do indicate widespread popular repudiation of the heritage of neoliberalism’s period of ideological ascendancy. The glory days of neoliberalism, when it was deemed to have mass appeal, are over. Now, neoliberalism can only get a hearing from the broad public if it is cloaked in a fake-populist pretense of anti-establishment insurgency. And that is where figures like Trump and Bolsonaro come in: they bear the cloak in which neoliberalism can conceal itself behind a deceptive rhetoric of rebellion against ‘the elites’ and empowerment of ‘ordinary people.’

Neoliberalism’s Crisis of Popular Legitimacy

Indeed, the key to today’s far-right resurgence is that it responds, not to the vulnerability of capital’s hegemony to a militant challenge from the far-left or the wider workers’ movements, but to the collapse of popular legitimacy of the political parties, the political assumptions, and the political institutions of contemporary “bourgeois” (liberal-democratic, pro-capitalist) electoral politics, brought on by decades of neoliberal policy consensus within official party politics. This legitimation crisis — recently expressed in the USA by such insurgent protest movements as the Tea Party on the right and the Occupy Movement on the left — has weakened the grip of mainstream ‘centrist’ parties over popular political activity across all classes other than big business. The epochal convergence of labour, liberal, and conservative political parties toward an “extreme centre” of consensus neoliberalism, entailing as it does the rupture of continuity of contemporary social democracy with the Keynesian version of welfare-state politics on the one hand, and the downplaying of ethnocentric nationalism and patriarchal ‘family values’ by establishment conservatism on the other hand, has severed the ties binding the masses on both the (mostly working-class) left and the (mostly middle-class) right to the official political process and its parties. This has opened up spaces to the left and to the right of the ‘extreme centre,’ for forms of political engagement rooted in the revulsion of the broad masses toward the centrist neoliberal project as a whole. The pervasiveness of this revulsion makes it impossible to win broad public approval for open, self-declared neoliberalism. There has to be an anti-establishment cloak of some kind, some promise of a fundamental rupture, for neoliberalism to gain a hearing. And figures like Trump, Bolsonaro and Erdogan take this as their starting-point.

Neoliberal Continuity? Or Proto-fascist Rupture?

But these considerations seem to necessitate that we choose between two competing analyses: Should we regard these far-right ‘strong man’ figures as fundamentally continuous with earlier champions of neoliberalism, substantively, even if they break with them at the level of rhetoric? Or should we regard them, perhaps more ominously, as present-day re-enactors of the fascist versions of pro-capitalist demagogy familiar from an earlier epoch? Applied to the case of the USA, the first option would have us emphasize Trump’s continuity with Obama and Bush at the level of policy, and discourage an undue emphasis on his use of cynical anti-immigrant appeals to boost voter enthusiasm among his ‘base’ of disgruntled middle class racists who reject ‘the political elite’ en masse. The second option, by contrast, would have us interpret Trump as representing a qualitative break with liberal democracy motivated by a proto-fascist rejection of key aspects of official politics and the liberal-democratic constitutional order. The question of which analytical tack to take is made more difficult by the fact that both sides accept, as a matter of course, both that Trump is a racist demagogue whose most ardent supporters are ‘alt-right’ fascists, and that he and his fellow rightists rely on the support of a ruling class that is uncompromisingly committed to the defense and intensification of neoliberalism

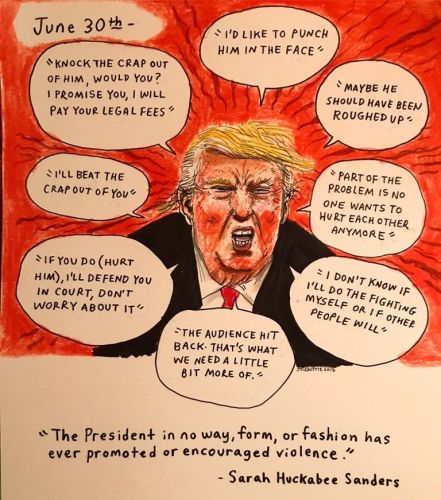

In truth, neither analysis — neoliberal continuity nor proto-fascist rupture — is wholly convincing. The problem with the ‘neoliberal continuity’ view is that Trump has clearly actively cultivated an alliance with grassroots militant fascists (the extremists who assembled at the ‘Unite the Right’ fascist rally in Charlottesville in 2017), and signaled with varying degrees of coyness and dog-whistling that he supports their use of extra-constitutional violence against the left, particularly against anti-racists, as well as the lawless persecution of migrant workers (for which he made a point of pardoning Sheriff Joe Arpaio). Trump is consistent about this. In one case, he encouraged a mob of his supporters to physically attack anti-racist protesters during one of his rallies, and promised to pay the legal fees for any pro-racism fighters. Later, he famously said that there were “very fine people” in the openly fascist, violence-oriented Charlottesville march — a comment he made after the murder of Heather Heyer by one of his supporters from a participating fascist organization. I could enumerate many other examples, but this aspect of Trump’s ‘footsie’ relationship with racist street-violence is well known. Given this aspect of his politics, it is hard to assimilate his political posture to the neoliberal mainstream. Trump’s distance from the mainstream is in this respect not only stylistic, but also substantive, and this lends plausibility to those analyses which emphasize his proximity to traditional fascism

But the discontinuity or ‘proto-fascist rupture’ view also has serious limitations. Trump’s primary political organization is the Republican Party, not one of the many ‘alt-right’ fringe groups, and he works closely with the same politicians that Obama and Bush negotiated with before him, people like Mitch McConnell, et al. In general, Trump usually functions as a conventional US President, trying to get legislation passed in order to help the richest and most powerful people get richer and more powerful. He has shown very little inclination to use the powers of his office directly to carry out state terror campaigns against immigrants, anti-racists or trade unionists, as we might expect a fascist government to do.

Is Trump a Fascist?

The upshot of these considerations is that it seems difficult to say with conviction either that Trump is or that he isn’t a fascist. It may help lend clarity to the discussion to set out a straightforward account of what we mean by the word ‘fascism.’ I define fascism as an anti-democratic regime or social movement, which (i) promotes a leader cult, (ii) claims exemption from constitutional constraints on the legitimate use of force, and (iii) promises an ethnically exclusionary type of national resurgence to be achieved through harsh repression against demonized ‘foreigners’ and ‘subversives.’

Is Trump a fascist, in this sense? If we take this question on its own terms, it can only be answered in the negative. To be sure, he clearly does demonize ‘foreigners’ (migrant workers, Muslims) and to a lesser extent ‘subversives’ (above all, ‘Antifa’), and he does promise national resurgence (‘make america great again’) to be achieved by harsh repression (‘build the wall’, the Muslim travel ban, sending troops to stop the migrant caravan, etc.). Moreover, it would be absurd to deny that he promotes a leader cult, because the hyper-emphatic promotion of his own claim to glory and greatness is by far his main preoccupation. However, in spite of this, Trump, on his own, is not fascist (in the sense set out above) because he does not claim exemption from constitutional constraints on the legitimate use of force, which is one of the key differences between fascists and other conservatives, whose politics otherwise overlap extensively. (For instance, it was a key difference between Hitler and the “Iron Chancellor,” Otto von Bismarck, who anticipated many of Hitler’s policy views, including annexationist pan-German nationalism and the demonization and persecution of religious minorities and political dissidents, but who remained compliant with constitutional constraints.) Trump shows every sign of being willing and able to pursue his far-right agenda within the confines of the constitutional order. So, it seems wrong to call Trump, individually, a fascist, or indeed to call the Republican Party a fascist party.

However, it has to be said that Trump does not operate individually, as a solitary political actor. And the Republican Party is by no means the only organized political force involved in Trump’s ascendancy. Trump himself and his party operate as part of a larger, de-centred constellation of both politicized networks and political organizations, united not always by direct organizational coordination, but instead by their shared affiliation to the Trump leader cult and their shared commitment to the rightist agenda of pursuing (white) national resurgence by targeting “racialized outsiders” (and to a lesser extent, anti-racists) for demonization, repression, and often violence. It is possible to think of Trump as one part of a larger array of political formations that collectively makes crucial use of extra-constitutional violence at the street level that he himself does not actively direct (even if he legitimizes it and provides public rationales for it, such as by declaring that some group should be seen as ‘enemies of the people,’ and so on).

Two-Track Fascism

When we take this larger context or array of forces into account, the question of whether Trump is himself a fascist seems inadequate. The better question would be: Is Trump operating as part of a decentred constellation of political forces which, taken collectively as a complex movement, comprises a political form that fascism sometimes takes today? To that question, the answer may be that, yes, Trump is integral to contemporary fascism in the USA, even if he or his Administration may not be per se fascist. This suggests an analysis that rejects both the neoliberal continuity view and the proto-fascist rupture view, and which instead shifts the focus away from the politics of the leader figure as an individual and toward the constellation of loosely aligned political forces in which the leader operates politically.

According to this “de-centred” analysis, the fascism that exists in the United States (which I’m treating as exemplary, i.e., as analogous to several other similar regimes and movements globally) does not follow the 1920s/1930s model exactly, in that it is not a unitary fascism, in which leader, party, state, street-fighting force, and popular support base are all united in one organized and tightly coordinated bloc. Rather, it is a two-track fascism, with (1) an electoral track, organized inside the Republican Party, closely aligned with Wall Street, where it pursues a policy agenda that cloaks deeply unpopular neoliberal measures behind ‘white nationalist’ rhetoric and high-profile ‘culture-war’ policy fights (about immigration, trans rights, Islam) that have mass appeal to middle class racists, and (2) a street-level track, organized outside of the official political process, in which racist militias and violent white ‘pride’ men’s clubs try to wrest control of the streets and the public sphere from anti-racists, trade unions, feminists, and other democratic forces, and (if they had their way) to create no-go zones for visible minorities (in this respect replicating the classical ‘Freikorps’ model of the völkisch movement in Weimar Germany). What binds the two tracks together is their shared affiliation to the Trump leader cult, and their shared project of ‘making america great again’ by demonizing and targeting migrant workers, Muslims, LGBTQ people, and others for persecution.

In this respect, fascism in the USA is a kind of mutation of the Tea Party movement. The Tea Party movement was crucial in pioneering the idea that a militant grassroots white-nationalist protest movement in civil society (that is, outside the state), with a middle-class base, a hostile attitude to the political process, and a deep contempt for mainstream politicians and liberal constitutionalism, could enter into an alliance with big business, based on both tactical policy convergence and a ruling-class commitment to offer funding for the protests. The Tea Party as such has largely disappeared, but under Trump’s leadership — and under the banner of the ‘alt-right’ fascist revival — it was reassembled in the form of a motley constellation of far right militias, white supremacy ‘pride’ fraternities, neo-Nazi revivalist cults, and other more or less radicalized MAGA-vigilante groups and individuals, informally but in most cases fanatically aligned with Trump’s electoral track project.

The fascists who operate in this extra-constitutional ‘street-level’ track know that Trump is on their side, and accept that he cannot fully say or do anything that his location in the official political process precludes. But they know that they, by contrast, are free from such political constraints. As the point was put by one Trump-inspired armed attacker, who recently carried out a terror attack on a synagogue in Pittsburgh, killing 11 people, “Screw your optics, I’m going in.” Because the violent, extra-constitutional, street-level track operates independently of Trump, it can carry out aspects of the MAGA agenda that Trump is assumed by the militant fascists to be tacitly favorable toward, but which he is unable to explicitly defend. For his part, Trump never tires of signalling his sympathy for their motives, if not for their every action.

The Limits of Today’s Two-Track Fascist Movement in the US

From this point of view, Trump’s “white nationalist” intervention in electoral politics forms an integral part of a single (albeit de-centred and dual-track) movement with the ongoing sequence of violent interventions by street-level fascists of the Charlottesville rally variety. These street-level fascist interventions include beatings, death threats, armed patrols, mass shootings, and assassination attempts. As ominous as this development is, it is important not to misunderstand the phenomenon of two-track fascism, in particular by overstating its capacities. Of the two tracks, the electoral track is the stronger and more potent, but neither track has accumulated capacities remotely comparable to those of Hitler’s Third Reich or the Italian Fascists under Mussolini. Wall Street neoliberalism is still by far the most powerful political force in US politics. In the US, to be sure, the Trump Administration has given fascist politics — and relatively open fascists intellectuals, like Stephen Miller and Steve Bannon — a relevance to mainstream politics that their ilk had been denied for generations. But both the street fighting and terror capacity of the street-level track, and the grip of Trump and his inner circle on the vast apparatus of the US state, remain rather limited. The parts of Trump’s policy agenda that find their way into US law consist almost exclusively of those elements of it that are acceptable to the Mitch McConnell types that comprise the Republican Party establishment (and their co-thinkers in the Democratic Party), who are all stalwart defenders of the neoliberal consensus: massive tax cuts for the rich, gutting forms of regulation once intended to limit capital in the public interest, the continuation of re-branded free-trade agreements, endless squandering of public money on military buildups and the expansion of police powers and prisons, and so on. Meanwhile, there is still no border wall, no reinstatement of a whites-only immigration policy, no wholesale rolling back of civil rights legislation, and so on. The ruling class still largely dictates what governments can do, and that means that the neoliberal agenda remains the driving force of US government policy. Meanwhile, the street level fascists are continually humiliated by powerful ‘antifa’ mobilizations that rout them in the streets and repeatedly drive them into tactical retreat, far more often than they succeed in winning the day. The fascists do certainly carry out killings and beatings, so I do not wish to minimize the threat they already pose, but they are by no means capable of exerting the kind of power over the streets that they aspire to wield or that more powerful fascist movements have wielded in the past.

In short, two-track fascism represents a grave and growing danger, but its freedom to maneuver is limited by the fact that the niche it has found near the centre of US politics hinges on its usefulness to the ruling class as a way to cope with neoliberalism’s chronic crisis of popular legitimacy.

Some Key Aspects of the Left Response

The response of anti-fascists to the present situation should be to navigate a course between the danger of complacency on the on hand, and the danger of panic on the other. Fascists are actually still relatively marginal, and most people reject their politics out of hand. But the roots of fascist upsurge in the legitimation crisis provoked by the neoliberal policy convergence of the extreme centre isn’t going away. As long as the anti-neoliberal, authentically anti-establishment far left cannot yet mount a credible alternative to the neoliberal centre (Mitch McConnell, Nancy Pelosi, et al.), the far right will try to fill the vacuum with the kind of fake-populist white-supremacist politics that fuels Trump’s ascendancy and energizes his street-level fascist collaborators. The main strategic implications of this analysis seem clear. I will highlight three points.

- First, it is necessary for anti-fascists to mobilize always and everywhere to try to deny the street-level fascists access to public space, making it effectively impossible for them to hold events in public. By driving them out of public space, we can isolate their core activists from the periphery of bigots that they want to recruit, demoralizing them and driving them back to the internet chat rooms and websites where they were largely confined before Trump’s election gave them a new confidence to organize openly. Realistically, we know that the police will always try to defend them and criminalize anti-fascist activity, and this makes our task more difficult. But with solidarity, militancy and determination we have shown that we can defeat them in the streets, more often than not.

- Second, since the strength of two-track fascism depends crucially on Trump’s alliance, at the level of policy, with Wall Street neoliberalism (mediated by Trump’s cooperation with the GOP establishment), it is necessary for anti-fascists to find ways to raise the costs of this alliance for Wall Street forces and the GOP itself. How to do so is a tactical question, which depends on the context. But generally speaking, anti-fascists have to expose the alliance and ensure that those who fund Trump or lend support to any aspect of two-track fascism are ‘tarred with the brush’ of fascist sympathies and are held accountable for the violence of the street-level fascists and the anti-democratic and white-supremacist features of Trump’s program and ideological posture. Trump’s funders, collaborators, and enablers all have to be exposed and held accountable. Brand-sensitive targets, such as corporations and politicians, are particularly vulnerable to this kind of pressure.

- Third, the far left has to work toward developing the capacity to hegemonize (gain leadership over and draw support from) the popular mood of revulsion against the hated neoliberal consensus of the extreme centre. In the US, it is obvious that the Democratic Party is hopelessly incapable of appealing to this sentiment, or rather it is completely uninterested in doing so because it is itself so deeply committed to the political project of upholding neoliberalism. By contrast, the Democratic Socialists of America, and before that the Sanders campaign, have tried to tap into the anti-neoliberal sentiment on the basis of some kind of left critique, with some degree of success. Whether the DSA (or Sanders) have the politics needed to follow through on these opportunities and develop a real challenge to both the neoliberal extreme centre and the far-right phenomenon of two-track fascism, is debatable, but this question is beyond the scope of the present discussion. What is crucial is just to be clear that defeating two-track fascism will remain a futile “labour of Sisyphus” unless the left can build itself up as a pole of attraction drawing energy and popular support from working-class revulsion against neoliberalism. Until our side develops that capacity, the right will continually benefit from anti-establishment anger that ought instead to be the main engine of left radicalization and anti-capitalist revolt.

Closely aligned with Wall Street? How does that square with Center for Responsive Politics report that the securities and finance industry has backed Democratic congressional candidates 63 percent to 37 percent over Republicans? The answer: it doesn’t.

You write: “Closely aligned with Wall Street? How does that square with Center for Responsive Politics report that the securities and finance industry has backed Democratic congressional candidates 63 percent to 37 percent over Republicans? The answer: it doesn’t.”

Actually, that’s not the answer. I’ll try to explain concisely. From a pre-scientific standpoint, especially one informed by the ideological assumptions that underwrite the capitalist electoral system, it will seem as though Wall Street support for *one* of “the two parties” is incompatible with Wall Street support for the *other* party. From a scientific-socialist standpoint, on the other hand, it is quite sensible to expect Wall Street support for one of these parties to be echoed in further support for its counterpart, as long as both parties participate in the longstanding neoliberal policy consensus of the extreme centre. Usually, the Republicans get comparatively more ruling-class money, followed closely by the Democrats. Sometimes, as in this election year, the ordering goes the other way (due mostly to Trump’s willingness to engage in trade-war bluffs with China and others, but also due to advance expectations of more wins by Dem candidates). But the chronic or ‘secular’ (long-term) pattern is constant: Wall Street support for both parties. So it is that, as reported in the WSJ on November 4, “Members of the business community…contributed $891 million to Democrats and $839 million to Republicans through Oct. 17.”

A second, less important but also notable aspect of your mistake: “Wall Street” doesn’t only refer (as you seem to suggest it does) to (1) the financial industry, but also (2) the ruling-class counterpart to the ‘popular classes’ signified by the expression, ‘Main Street’; and (3) the class of investors who participate in the NYSE and similar stock exchanges (by no means only in NYC).